|

| Figure 1 – Tents at the 1916 Fort Prairie Pest Camp |

Introduction

pest (n.)

1550s (in imprecations,

"a pest upon ____," etc.), "plague, pestilence, epidemic

disease," from French peste (1530s), from Latin pestis "deadly

contagious disease; a curse, bane," a word of uncertain origin. Meaning

"any noxious, destructive, or troublesome person or thing" is attested

by c. 1600. Pest-house "hospital for persons suffering from

infectious diseases" is from 1610s. [1]

Quarantining those stricken with

contagious diseases has been a common practice since ancient times, and continuing into

the 20th century, these temporary quarantine camps were commonly

identified as pest camps. Sometimes referred to as a quarantine camp, pest

house, pest grounds, smallpox camp, tubercular camp, yellow fever camp or any

other infectious disease the quarantine was intended to confine. But they all

had the same attributes in common; they were temporary impoundments hastily

assembled when a community believed an epidemic was emerging, and they were normally

placed outside of a town’s limits is less populated areas.

While tuberculosis, or consumption, was deadly it did not have the outward horrific physical attributes as smallpox. Smallpox in some of the most severe cases, if one survived, resulted in permanent scaring or disfigurement. There were also lasting social effects from the disease that many survivors experienced. One historian’s account of her family’s experience with smallpox in Plano, Texas during an outbreak in 1895 says that “The Collinsworth family had a stigma on them for many years afterward…Their neighbors were frightened and avoided them.” [2]

Travis County’s most often cited

history chroniclers, Frank Brown, and Mary Starr Barkley left no record of the

pest camps and only one reference in each to smallpox. Dr. James M. Coleman’s,

Aesculapius On the Colorado describes in brief, activities of doctors treating

infectious diseases in a 1890-91 camp but does not elaborate on the many

locations in the county. So why were Brown and Barkley silent on the subject? It

was clearly by their choosing.

Brown’s work was based largely

on the same sources used to create this report. Like George Washington’s

portraitists that chose to not include his smallpox scars in their life

portraits of the president, Brown and Barkley left the “bad” news out. Unless

the bad news were accounts of the white man’s enemies, like “savage” Indians or

Mexicans attacking and killing whites. Those stories usually end with the grandiose

defeat of the enemy by brave and noble Texans. Smallpox, on the other hand, was

an enemy that could not be defeated by Texas Rangers or guns, the only defense

was to hide from it and hide those infected with it, in pest camps.

As much as people feared the disease, they also feared being sent to a pest camp. Many went willingly but many resisted and hid their disease believing they would be marked and shunned and that the camp was a death sentence.

Smallpox inflicted all ages, races and social classes but was even worse for minorities because, forced by poverty, often one or more families lived in very cramped conditions with inadequate shelter so when one became infected, everyone in the household did. A 1914 report from Mrs. Nellie Holden, secretary of the United Charities of Austin describes this type of situation. She visited a Mexican family living near the river south of the city and described the residence and an old, ramshackle, dilapidated hovel, in which lived 11 children and 8 adults, “all huddled up in a space scarcely large enough for two” and “in one corner an old Mexican man, far gone from Tuberculosis.”67 In 2012 author Jim Downs described the greatest unrecorded casualty of the civil war was the death from disease of thousands of African Americans during the war and decades thereafter.[3]

Ethno-medical beliefs also contributed to the spread. In 1918 when smallpox broke out in a Mexican community at Garfield the county sheriff took 32 in custody to the pest camp. Authorities attributed the rapid spread among the group was due to the Mexicans attempting traditional medicine and religious practices which resulted large groups in close quarters being infected. In 1899 when a smallpox outbreak hit Laredo, Tx W. T. Blunt, State of Texas health officer arrived to take over efforts to control the spread including vaccinations and fumigations and burning of personal effects that could not be fumigated. When the Laredo residents resisted the Texas Rangers were called in to force residents to comply with the medical officer. The chain of events led to one of the most tragic smallpox riots in Texas, the death of one man and the wounding of thirteen.[4]

Adding to the social stigma of

the diseases and the pest camps was the way in which the camps were organized. Like

a prison they typically had armed guards to keep the sick in and visitors out. One

account says visitors were not allowed any closer than 75 yards from the camp. Sometimes

the sick in the camps were often described as inmates which further emphasized,

they were in custody of their guards.

When guards were not present sometimes

inmates would escape usually occurring when the infected were in advanced

stages of severe smallpox, the patients in agony and fevered delirium would

break out. Some to run into nearby bodies of water to seek relief for the pain,

others breaking into nearby houses to seek a place to die in comfort. One man

in Taylor isolated in his own house is said to have committed suicide to escape

the horror of the disease by pouring kerosene over himself and his bedding and

setting himself on fire.

Fear gripped communities when smallpox or tuberculosis arrived, and pest camps were established each time it visited. Numerous Texas counties had pest camps and cemeteries that were established on the pest camp grounds. Examples are the Pest House Cemetery, Lamar County, Collinsworth Cemetery in Collin County, Pest House Cemetery a.k.a. Ellis County Poor Farm Cemetery, City of Paris Pest House Cemetery in Lamar County and Pest Camp Burial Grounds, Colorado County.[5] This list is not all inclusive and, probably every county in Texas had pest camps and burial grounds associated with them.

The purpose of this article is not intended to illustrate parallels with what the world experienced beginning in 2020 with COVID-19. Journalists across the US reflected on epidemics of the past and the similarities of government actions then and now. But the similarities are there, quarantines, social unrest, stigma of being infected, denial of some citizen groups of the existence or severity of an infectious disease and fear and suspicion of immunization and distrust of government action. The maxim that history repeats itself is undeniable.

Pest Camps locations from 1881-1937

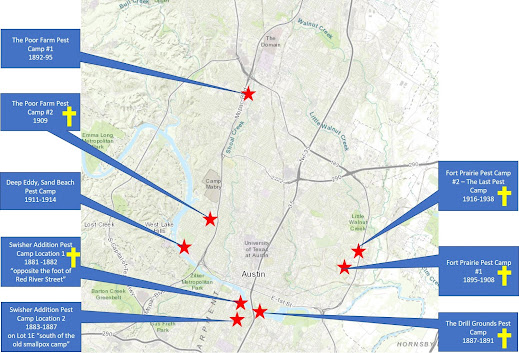

From 1881-1937 pest camps have

been established in eight locations in Travis County as shown on Figure 2 and

in some cases, burials at the camps.[6]

Following in chronological order are descriptions of each of the locations. With the exception of the

Fort Prairie Pest Camp the names used to describe the camps are based on their

location.

|

| Figure 2 - 1881-1937 Travis County Pest Camp Locations Yellow crosses indicate burials reported in the camp. |

1881-1882, Swisher Addition Pest Camp No. 1

Pest camps probably existed earlier

in Travis County, but it was not until 1881 that Austin newspapers begin

consistently reporting on them. An August 1881 report stated there had not been

a case of smallpox in Austin for two yearsF [7],

but by December, Austin’s two year stretch of good luck had run out as

evidenced by an Austin City Council resolution:

Resolved: That it is

expedient and demanded in the protection and the health and lives of the

citizens of Austin that the cases of smallpox now in the city, and those

exposed to the contagion, to be removed from the city, and suitable tents be

erected for their accommodation…That steps already taken by his honor, the

mayor, in having a guard placed in charge of the premises infected [and]

erection of flags of warning.[8]

Reported on the 22nd

of December was the case of a family that had arrived in the city from Iowa

settling in a house on North Avenue near the Swedish Church. Two of their

daughters ages four and eight fell ill and were diagnosed by the city physician

with smallpox. The next morning the board of health met and decided to have

flags put up and guards put around the infected premises.[9]

It was standard procedure for city and county health officials to first attempt

containing isolated smallpox cases by quarantining families in their home. Officials

would put up yellow warning flags around the house and armed guards to keep

visitors out and the infected in. However, when epidemic proportions developed

there were not enough resources to guard every house. That was the tipping

point to begin moving people to the camps, and they took whole families, often

families not even showing signs but that had been exposed to an infected

person. Days after the first report on December 22, health officials began moving people to the camp and by the 28th

there were five more cases of smallpox “at the tent across the river”,

no details had been given of how many were there before the 28th F[10]

Eight miles north of the city in

the Swedish community around Decker Church smallpox had begun to spread. On January

5th, 1882, a report ran in the Statesman that Reverend Newberry

Minister of the Decker Church had been stricken with the disease and that he

had been associated with a Mr. Lundell and other Swedes of the original

smallpox cases that had been sent to the tents the previous month. Two groups

of Swedes were the Enquist and Olsen families of which the city physician

stated Mr. Enquist’s daughter, Amanda, was not dead yet but not expected to

live. The next day she and a 1 ½ year old son of the Olsen family died. The

doctor also reports that both were buried immediately, “in the neighborhood

of the camps”.[11]

In February after Mr. Enquist

and Mr. Olsen had recovered, they asked Austin City Council to be allowed to remove

their children, who had died at the camp and were buried there. The city

physician, Dr. Matthews, opposed the request stating that “The parties

employed in exhuming the bodies would be exposed to infectious exhalation

emanating from the decomposing bodies in the exposed coffins, which are so

poorly constructed as to permit the escape of noxious gasses from their

interior. The city sexton and other employed in interring these bodies would

also be exposed in a similar matter.” Dr. McLaughlin disagreed with

Cummings stating that with good scientific precaution no danger might result.

It was called to vote and there being a tie vote, the president, Dr. Cummings,

voted in favor of the resolution, so the requests were denied.[12]

In his January 18 report to the

mayor [13],

the camp physician, Dr. Denton, reported the names of those in camp and their

status, including deaths. He listed the

names of 38 people that had been or were still in the camp and those that had

died. Following are the names of deaths including the Eqnuist and Olsen

children:

Iza F. Olsen, female age 9, died December 22, 1881 (died in the city)Clara A. Olsen, female age 4, died December 22, 1881 (died in the city)John E. Olsen, male age 1 ½, died January 5, 1882August Cedarglad, male, age 40 died January 5, 1882Amanda Enquist, female, age 9 ½ died January 10, 1882Peter Neiberg, male, age 64, died January 10, 1882

Miss Ida Peterson, female, age unknown, January 14, 18823F[14]Terbable, male, age unknown, January 5, 1881[15]

On February 9 the Austin Weekly Statesman ran the lengthy smallpox report of Dr. Denton who had been attending the ill at the camp. The report included the following table summarizing the illness and deaths.[16]

|

By the end of February, the

epidemic had subsided, and the camp dismantled.

Note that there is a list of

deaths in the camp and reported burials “in the in the neighborhood of the

camps”. Quarantine applied to the living and the dead and it was common

practice to burying the dead in or near the camps.

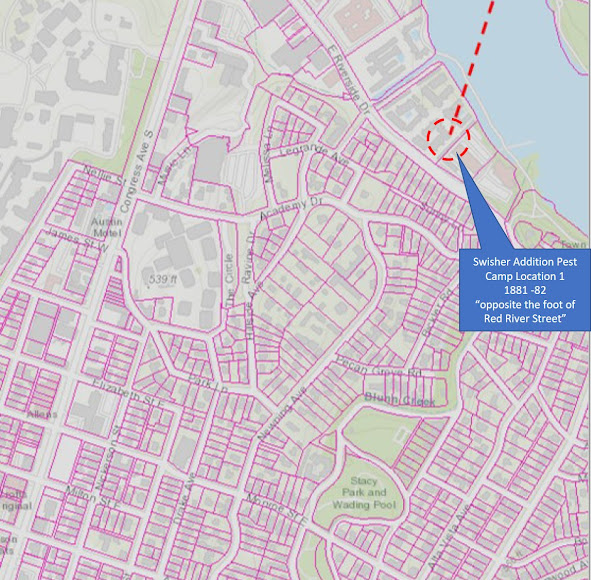

When the outbreak started in

December the Statesman reported the smallpox cases stating, “They are to be

placed in tents south of the city, almost directly opposite the foot of Red River

street.” [17]

Using the 1877 Swisher Addition Plat 16[18]

superimposed over a current map, the 1881-82 camp location described as

opposite the foot of Red River street, or across the river, places the camp on

a 118 6/10-acre tract of land owned by John

M. Swisher. In January 1885 Swisher sold this tract to Charles A. Newning who

in turn immediately platted Fairview Park from the tract.

Projecting

a straight line across the Colorado River from Red River street places the camp

somewhere on part of Swisher’s Addition on a tract owned by John M. Swisher:

|

| Figure 3 - 1877 Swisher Subdivision Plat Pest Camp Location No.1 |

|

| Figure 4 - Current map showing approximate location of the Swisher Subdivision Plat Pest Camp Location No. 1 |

1883-1887, Swisher Addition Pest Camp No. 2

From 1883-86 the newspaper

reports of smallpox were scarce compared to the 1881-82 outbreak but there are

enough to know it made its presence and the camp was still in use. In 1883 the

city was trying to be better prepared for an outbreak by appropriating funds to

purchase land and appointing a special committee to find a suitable location for

a pest camp. In March, the committee had accomplished their goal purchasing a “parcel

of land on which to erect a pesthouse”. They purchased “eight acres

across the river, just south of what is known as the “old smallpox camp” paying

$15.00 per acre.[19]

While we can approximate the 1881-82 camp, there are no deeds or maps defining the

exact location. But with this transaction the camp can be pinpointed. The description

of the tract as south of the old (1881-82) smallpox camp is another datapoint

supporting the estimated position of the old camp. The 8-acre tract the city

had purchased was Lot 1E of the Swisher Addition.[20]

Revising the map previously presented with an overlay of the Swisher Addition

and highlighting the 8-acre tract aligns with the bearings described as south

of the old camp.

In 1886 one Statesman subscriber

expressed an opinion common across the country that would be repeated often in the following decades; people do not want pest camps in their

neighborhood.

“The pest camp should be

located on some worthless spot of ground, remote from habitations, and where

there is no likelihood of settlement. Such places can be had near Austin. The

pest camp, as now located, is surrounded on all sides by the most beautiful

building sites on the continent, and they are rapidly occupied.”[21]

The following day another

subscriber wrote complaining that camp detainees had left the camp and were

roaming over the neighborhood near the residence of a Mr. Malone which was some

300 feet from where city authorities had located the camp. Another resident in

South Austin, a Mr. W.H. Bell was said to have reported there was no guard at

the camp.[22]

Although

the camp was originally established on a subdivided tract in a sparsely

populated area, it was filling up around it and citizens wanted it moved.

|

| Figure 5 - 1877 Swisher Subdivision Plat Swisher Subdivision Plat Pest Camp Location No. 2 |

|

| Figure 6 - Current map showing approximate location of the Swisher Subdivision Plat Pest Camp Location No. 2 |

The theme of “not in our neighborhood” ran strong everywhere and in some cases resulted in violence. In 1895 when county authorities began to erect a pest house five miles outside Winchester, Kentucky farmers turned out “enmasse, armed with Winchesters” to prevent the pest house from moving to their midst. Carpenters had almost completed the house before a mob gathered and when the sheriff arrived to protect the carpenters, he was driven back to town by two hundred armed men. The next night the farmers burned the pest house down and set guards around the town to prevent a smallpox case from being moved out of the town. The farmers insisted the town stop shipping contagious diseases from the town to the country districts.[23]

Travis County was growing at an escalating

pace so securing a camp location “remote from habitations” was becoming

increasingly difficult so moving the camp was a recurring theme.

The final push to relocate the

camp from the Swisher’s Addition came in November 1886 at the request of real

estate developer Charles A. Newning. He was in the planning stages of

re-subdividing portions of the Swisher Addition he had purchased that adjoined

his Fairview Park development. To do so he was requesting certain roads be

closed because they interfered with proper alignment between the subdivisions,

and since the pest camp tract was surrounded by the Swisher Addition tracts

that he planned to re-subdivide, he petitioned the Commissioners Court to sell

him the land and relocate the camp.

Newning’s lengthy petition was

read to the Commissioners Court on February 19, 1887. The following excerpt of

the petition describes the pest camp, which was the 8-acre, Lot 1E tract the

city purchased in 1883:

“For some time there has been

located on the south side of Fairview Park a tract of land owned by the County

and City together which the City is in the habit of using as a pest ground…The

location of the pest ground at this point is detrimental to the health of the

locality and largely tends to prevent the proper settling of the county. The

land is almost entirely waste…I will deed to the county lots 7&8, Block 32 Swisher’s

Addition and guarantee to construct thereon to be finished on or before the 15th

day of August 1886, a school building…provided the County will in turn give me

a deed fee simple for their one-half interest in said pest ground. I will say

that I propose to help the county build the school in any event, but I feel that

Justice demands that the danger of the pest grounds should be removed.” [24]

Newning’s petition was granted

and the pest camp tract deeded to him.[25]

Along with the rest of the Swisher Addition, the pest camp tract was re-platted

and subdivided. No records of deaths and burials on the Lot 1E pest camp tract have

not been found.

1887-1891 The Drill Grounds Pest Camp 1887-1891

During 1887 there were isolated smallpox

outbreaks around the state but very few reported in Travis County. By the winter

of 1888-1889 there was enough of an outbreak to establish a camp, so the city

and county again sought a new location. In January 1889, the city passed

a resolution asking school trustees to use the old city hospital which the

school board agreed to, but there is no record the building was ever used for

as a pest house. [26]

Instead the city erected tents outside of town on a tract called the drill

grounds. [27]

What they described as the old drill grounds were in 1888, the location of the grandest celebratory event in Texas during the 19th century. The grounds were at Camp Ross which was established in early 1888 as the encampment site for the May 1888 new capitol building dedication. The Statesman newspaper described the dedication event as “Never in the history of our city, never in the history of our state, was there another such day”.[28] The image to the right was an artist’s interpretation representing “a view of the drill grounds as taken form a private box in the grandstand, the military passing in review – the tents to the right in the distance, and the new capitol building to the left in the far background”. [29], [30] No one would have dreamed that just months after the dedication that the stately row of military tents would be replaced with the humble tents of a pest camp.

Figure 7 -1887 View of the Drill Grounds. Courtesy of the Austin History Center

The location for the drill grounds was made in September 1887 by an incorporation of Austin businessmen named the Texas International and State Drill Association.[31]. By January 1888 they had named it Camp Sul Ross which was later shortened to Camp Ross30F30F30F30F[32] They initially selected a +/-70-acre subdivision named the Riverside Addition which was owned and platted by a wealthy Austin businessman by the name of Frank Hamilton who was also on the board of directors of the drill association. It was a subdivision of outlots 34, 36, 47, 48, 58 and 67 in Division “O”. The board later added an additional 40-acres to the east of Riverside making the encampment 120-acres.[33]

|

| Figure 8 - The Drill Grounds Pest Camp location 1887-91 |

In the winter of 1890-1891 an outbreak hit Houston and within a short time was sweeping across the state. In his report to city council in early January, Austin’s city physician, Dr. Graves, suggested that a location for a pest house or camp be selected in case smallpox should stray into the city.[34] They promptly appointed a police officer named Palmer to set up a camp, affixed tents and had nurses in readiness.[35] This camp also had a unique distinction from previous camps in that it was referred to not just as a pest camp, but also as Camp Palmer for the officer in charge of the camp.[36]

By January 16, 1891 smallpox

cases had arrived in Manchaca and Austin. A travelling salesman that was a

tenant in the Evan’s building returned from Temple and was taken sick with

smallpox. The concern about his occupancy in a public building caused his

removal to the camp. City physician Dr. Graves went to Manchaca to see the

smallpox patient, Mr. Blue Hamitt. Graves reported back that Hamitt had

smallpox in the worst form and would die. Of most concern was that Hamitt had

been in Austin a few days prior visiting a Mr. Allen who also contracted the

disease. Camp Palmer was described to be on “the old drill grounds” and that two

tents were fitted up, floored, and boarded up four feet.[37]

The old drill grounds was the same tract the city used during the 1888-1889 outbreak.

Like its predecessor, Camp

Palmer received its share of complaints from the neighboring community when one

of the patients escaped to roam about the area. A Statesman article column headline

read “DANGEROUS CARELESSNESS AT CAMP PALMER PERMITS INFECTED PERSONS TO

ESCAPE, Citizens Loud in Their Complaints”. The citizens of the area also

complained about transporting smallpox patients from Bull Creek and the Terrell

place to the city stating, “it is part of the wisdom to take smallpox from

densely populated districts into sparsely settled neighborhoods” and that

they should do the opposite, send the infected to Bull creek.[38]

On April 18, 1891, The State

Health Officer visited the camp reporting that there were only five cases of smallpox

in the camp but about 40 were confined there that had either recovered or had

been exposed to the disease and are kept in isolation.[39]

On May 20, 1891, the newspaper

declared “Camp Palmer to break today” and included accolades issued to Sergeant

Palmer and Dr. Graves for their services at the camp. The article continued

stating that there had been a total of 46 had been quarantined at the camp of

which 36 developed smallpox and 4 died. It also included a table comparing

statistics for Galveston, Houston, Waco, San Antonio, and Austin. The writer of

the article attributed Austin’s lower death rate to isolation in tents opposed

to buildings.

A month after the camp was

closed two Travis county men filed damage claims with the Austin City Council

for losses due to loss of the use of their farms “on account of the smallpox

camp being so near the same as to make the cultivation of the same dangerous.[40]

Two years later Austin entrepreneur William H. Tobin submitted a claim to

Austin city council for damages to his property from Palmer’s pest camp on the

drill grounds. The August city council meeting minutes record the following:

“Claim of W.H. Tobin for $400

damages on account of a smallpox camp established by the City of Austin on his

land, [Out] Lot 67 and the burial of the remains of the persons who died with

the disease in the street in front of said land during April 1891.”[41]

In November 1893 City Council

appropriated $200 damages to pay Tobin’s claim. His Outlot 67 was part of the

Riverside Addition (the old drill grounds) that he purchased from Frank

Hamilton.[42]

With the closure of Camp Palmer

and complaints of its location Travis County Commissioners appointed committee In

November 1891 to select a “suitable location for a pest camp”.[43]

The hunt was on again.

1892-1895, The Poor Farm Pest Camp No. 1

Travis County appears to have

been spared any large smallpox outbreaks from 1892-1899 with only one case located

in a pest camp located at the county poor farm in April 1895.[44]

Richard Denney describes the location of this poor farm in his TCHC Blog post,” Poor Farm: Travis County's First”.[45] The county purchased this tract 1879 but had seldom used it as a pest camp.[46]

|

| Figure 9- The Poor Farm Pest Camp Location No. 1 |

1895-1908, Fort Prairie Pest Camp No. 1

County officials may have used

the poor farm because of not yet having procured land dedicated for a pest camp,

but it was not a permanent solution. In February 1895 County Commissioners resumed

the effort to select a pest camp site authorizing the County Judge $400 to

purchase land for a pest camp. By April commissioners purchased 8 acres south

of Fort Prairie and erected a house and fence.F[47],F[48],7F[49]8,[50],F[51]

The fall and winter of each year from 1899-1904 there were a smallpox outbreaks requiring the use of the Fort Prairie pest camp. This tract later was used as a pauper cemetery and eventually named by the county as the International Travis County Cemetery. Of the 8 pest camp locations in Travis County, this is the only one where burials have been recognized during its use as a pest camp that is still preserved as a cemetery.

|

| Figure 10 - Fort Prairie Pest Camp Location No. 1. (Now the Travis County International Cemetery) |

1909, The Poor Farm Pest Camp No. 2

When

the need for a pest camp sprang up in early 1909 the county set up the tents for

a pest camp at the new County Poor Farm.0F[52]

The County had sold the old poor farm northwest of the city the previous

October 1908 and purchased a 40-acre tract directly west of the city F[53],[54]

In addition to using the new poor farm as a pest camp, commissioners also had

their eye on it for a cemetery when in February they went there to “locate a

burial ground for paupers”.3F[55]

Why they chose to place the camp

there it instead of the Fort Prairie site that they had owned since 1895, is

not recorded but it did not take long for its West Austin neighbors to complain

about it.

In March, C.J. Armstrong, president

of the West Austin Improvement Club and spokesman for the West Austin citizens,

appeared before the commissioner’s court protesting the location of the camp. Commissioners

voted in support of removing the danger with orders to remove at once all the

smallpox patients back to “its old place at Fort Prairie” (the 8-acre

tract identified in the previous section as Fort Prairie Pest Camp #1).[56],F[57]

|

| Figure 11- The Poor Farm Pest Camp Location No.2, 1909 |

1909-1910, Fort Prairie Pest Camp No. 1

The last cases of smallpox and fatalities at this Fort Prairie camp were two deaths and burials in August 1910.[58] In 1911 there were outbreaks across the state, but Travis County had very few and no reports of pest camps.

1 911-1914 Deep Eddy, Sand Beach Pest Camp

Sometime in early 1911 a tent

was purchased by a man ill with lung disease. He pitched the tent along the

Colorado river on land owned by the city shown on early maps as the Sand Beach Reserve.

This lone tent was the beginning of a pest camp. Under the leadership of Mrs.

Nellie W. Holden, the United Charities of Austin grew and equipped the camp that

would be used for the next four years for tuberculosis and smallpox patients.7F[59]

In early 1912 a significant

smallpox outbreak was building in Mexico and through the Texas border towns,

resulting in many cases banning trains form those areas. In March, a Statesman

Article headline read “MEXICANS QUARANTINED”, carload of them under guard

out on “Sand Beach”. Onboard a I&GN train from San Antonio were twenty-one

men, women and children said to be Mexican refugees bound for north Texas. They

apparently knew one of the children had contracted smallpox, but the passengers

had concealed her until “the brakeman observed a small, mottled arm

protruding from under cover”.

At the depot the railroad

physician, Dr. Granberry, pronounced the case as genuine and a second case was

developing. The City Health Officer, Dr. R. M Wickline, set up a quarantine parking

the railcar and its occupants near the car stables of the street railway

company. At this point discussions commenced as to establishing a pest camp or

leaving the Mexicans in the car.F[60]

Two days later the doctors announced that a “pest camp would be established at

some point near the river bank, where there will be the least danger of

infection to the city.” F[61]

The next day the passengers were removed from the car to a guarded pest camp on

the river bank and were reported to be comfortably sheltered in tents with

floors.F[62]

The 3 year old girl who died 24 hours later.1F[63]

This camp closed about the end of March.

In October, a tuberculosis

outbreak prompted the United Charities of Austin to reopen the riverside camp

used earlier that year.2F[64]

By November there had been six inmates of the camp and one death. City council

discussed the location stating it consisted of six tents, is on the river beach

a short distance below the city powerhouse. They recognized it was not the best

choice but was regarded as a temporary location as no other is available at the

present time. Discussion again looked to establish a permanent location below

town.[65]

In

June 1913 city council discussed moving the camp again to either the county

poor farm or the tract the county owned in Fort Prairie, but it never came to

fruition.[66]

The sand beach camp was still in use by August with 3 patients remaining in camp

and 2 recorded deaths.[67]

Just weeks away from the

completion of the rebuilt Colorado River Dam in November 1914, the tuberculosis

camp “at Deep Eddy was swept away by high water”.[68] Available records do not indicate where

the patients were housed during 1915.

No records have been located to

determine an exact location for this camp and although one news article states

it was at Deep Eddy, there is no indication that it was on the Deep Eddy

property owned by C.A. Johnson and family that A.J. Eilers purchased in 1915

and developed as the Deep Eddy Resort. Based on it being described as on the

river beach a short distance below the city powerhouse it was most likely upstream

from Deep Eddy between it and the dam.

|

| Figure 12- Deep Eddy, Sand Beach Pest Camp Location 1911-1914 |

1916-1938 Fort Prairie Pest Camp No.2 –

Saint Joseph's Camp

For

the sixth straight year another broad scale smallpox epidemic was beginning to

sweep the country and getting alarmingly close to Austin in the surrounding

communities. Having been expressed in various ways and many times before, it

sounded familiar when a Statesman column headline announced, “CITY AND

COUNTY PROPOSE TO HAVE JOINT PEST CAMP”. It went on to state the city

physician and his assistant, Drs. S.A. Woolsey, and R.V. Murray, in company

with Mayor Wooldridge were planning to meet with county commissioners to

discuss the establishment of a pesthouse or camp for smallpox patients.[69]

The deed for the 11-acre tract purchased by the County Judge D.J. Pickle was recorded on May 5 but they had obviously selected the site in late 1916 as reports of activities at the pest camp a few miles from town in begin appearing in February 1917 newspapers. [70],[71] By June 1st the camp was announced to be closed. Since the previous November there had been 160 smallpox cases and thirty-five deaths.[72],[73]

|

| Figure 13 - The Fort Prairie Pest Camp Location No. 2, an 11-Acre tract purchased by the county in 1917. |

A 1984 cultural assessment of an African American cemetery in the Westlake Hills area describes another pest camp in 1916 that had been set up around the cemetery as a pest camp for black members of the Austin community and that when they died, they were buried in the cemetery. The description was provided from an interview of descendants of an African American Jackson family that are buried there.[74]

Research for this report found no evidence identifying a pest camp at this location nor for camps specifically for any race group. All evidence found during research for this report indicates that the pest camps were the only institution where race, gender, age, or social status found no bias, and all those inflicted with disease were sent to the same quarantine camp. There may have been separate wards, or tents separating race but there are no records documenting separate camps.

By March 1917 small Pox became an epidemic prompting Travis County officials to ask the Daughters of Charity to help care for these patients at a camp about seven miles north of the city limits. This camp was knows as the “Pest Camp” and “Fort Prairie” but the Daughters of Charity called it “Saint Joseph’s Camp”. Two Daughters of Charity and five nurses from the Seton Infirmary School of Nursing went to the camp to care for the patients and they remained there for ten weeks.

The Daughters of Charity that probably worked at the camp were Sister Lucia and sister Monica. The names of some of the nurses that worked at the camp were Frances Nowaski, Esther Berg, Virginia Woods, (unknown first name) Wrench, (unknown first name) Larkey. Nowaski, Berg, and Woods were student nurses in their second year at Seton Infirmary School of Nursing. No information was found about Wrench. Larkey is probably Otille Lorke, who graduated from Seton in 1909.

Seton Hospital supplied nurses for the Fort Prairie camp and one of them was a young graduate nurse assigned there in 1916 by the name of Leonora Annie Goetzel Crawford. She served at the pest camp through 1917 and then at Seton during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic. The photographs Leonora had of the Fort Prarie Pest Camp what may be the only photographic record of any Travis County smallpox camp.

|

Figure 14 - Leonora Goetzel Crawford, Graduate nurse at the Fort Prairie Pest Camp, 1916 |

|

| Figure 16 - Fort Prairie Pest Camp, 1916 |

In 1918 Leonora was among many Red Cross nurses that volunteered for service in WWII. She and 5 other nurses were assigned to unit 669 in October 1918 crossing the Pacific to Japan and then on to Siberia.

|

| Leonora Annie Goetzel |

Leonora was born October 15, 1884 to Ernst Hugo Goetzel & Marria Louisa "Marrie" Schachtner in New Braunfels, Comal County, Texas. In 1924 she married Arthur Bornefeld Crawford. They had one daughter, Diane Crawford, born October 2, 1930. Diane died in San Antonio on October 16, 2021. Leonora died in San Antonio on October 16, 1982.

While the camp had been closed in June residents in the vicinity were not happy with the county bringing a pest camp to their neighborhood. They arrived at the commissioner’s court on September 1, 1917 filing a protest the moving of the pest camp from “the property originally purchased by Travis County for that purpose about 25 years ago to the place near the Austin & Webberville Road easterly from Fort Prairie.”[75] The petition was signed by twenty white and black Fort Prairie residents. The property the petition described as originally purchased for a pest camp was the 8-acre tract that the county acquired in 1895, now the Travis County International Cemetery. No record has been located that would explain why the city would not have used the tract, but it may have been because it was so full of burials that there simply was not enough space for a camp. No action was taken with the petition to move the camp again.

|

| Leonora's Seton Nurse's School Pin |

|

| Figure 15 - Cemetery where smallpox victims were buried during the 1916 outbreak. Probably located on the Pest Camp grounds where the TB sanitorium would be build in 1938. |

When the 1917 smallpox out break had ended the county, unable to induce the Sisters to accept compensation for their services, gave them a gold medal in commemoration of its appreciation for their splendid public services. The medal was a disc of rough gold bearing a raised Maltese cross. Five small tents and a mesquite tree scene represent the tented city near Fort Prarie, where the camp was situated. The moto, "servio sine ostentatione" (I serve without ostentation), is inscribed upon the disc, and around the edge are the words, "St. Joseph's Pest Camp, Travis County, 1917"

The nurses who served at the camp and who received medals were: Misses Esther Berg, Otildio Larke, Frances Nowaski, Virginia Woods and Anna Roensch. 74F74F74F74F[82]

This report is focused on the pest camps that were established outside the city of Austin but it would not be complete without mentioning a camp established in 1918 on the street outside Seton Infirmary in Austin. The camp was named Camp O'Reilly for the beloved Seton Chaplain Father Patrick (Pat) J. O'Rielly. The tent city was unlike the pest camp tents in that they were not specifically quarantine facilities but resulted because so many became ill during the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic that Seton Infirmary simply ran out of room for patients. Father Pat and the Sisters of the Daughter of Charity served both the spiritual and medical needs of the many sick during the 1917 smallpox outbreak and the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic.

The Fort Prairie camp site continued to be used on a through 1938 as both a smallpox camp and a tuberculosis camp.

No records exist of burials at the Fort Prairie camp or whether the burials were moved from the grounds. A few names were determined by review of death certificates from 1915-1918:

Date of Death, Name, Sex, Race, AgeAugust 18, 1915, Lollie White, Female, Colored, 8March 9, 1917, Marguarette Brown, Female, Colored, 2*April 14, 1917, Lilla Cook, Female, White, 37April 14, 1917, Joe Rodriguez, Male, Mexican, 21April 15, 1917, Sam Crockett, Male, Negro, 45April 16, 1917, James Starr, Male, White, 38April 18, 1917, Ross Shaw, Male, Negro, 58April 20, 1917, Neal Sisk, Male, White, 3April 21, 1917, Gussie Shaw, Female, Negro, 19April 23, 1917, Louise Shaw, Female, Negro, 52*April 24, 1917, MA Sexton, Male, White, 51*April 25, 1917, Alice Purcell, Female, White, 41April 15, 1918, Anthony Rodriguez, Male, Mexican, 14Asterisk indicates an obituary was also found in The Austin American.

In 1937 interest began to grow in establishing a new Tuberculosis Sanatorium with a formal campaign launched on February 16, 1938. By October, the volunteer organization had secured enough funds to hire an architect, city council appointed well-known local architect, David C. Baer. There were three locations suggested for building the sanatorium but one, offered by the commissioner’s court, was the Fort Prairie site. The original 11-acre site was expanded in 1936 when the county purchased the adjoining 6-acre John Grove tract less some right-of-ways it was then 16-acres and the commissioners offered free use of the land for a city-county tuberculosis sanatorium. It was described as having had a main building and some smaller building which were removed after the main building had burned. These events brought the formal end to the last pest camp in Travis County. Construction started on the new sanatorium started in December 1938.

At the same time in 1938-1939 that

the county was planning the tuberculosis sanatorium, county commissioners had

decided to sell the 40-acre poor farm west of town. Funds from the sale would

be dedicated to help support building the new tuberculosis sanatorium. This

poor farm had been used as a pest camp in 1909 and at the same time in 1909 county

commissioners surveyed the poor farm for use as a pauper’s cemetery. The farm

sold at public auction in June 1939 and was deeded to Westenfield Development

Co by County Judge George Matthews.[76],[77]

Almost immediately Westenfield subdivided the tract filing the plat as

Tarrytown No 6. Roads were cut and houses erected before the end of the year.

Apparently, the commissioners

1909 inspection of the poor farm tract for a pauper cemetery resulted in using

part of it for that purpose. A 1967 Statesman full page article titled “a

disgrace…” by staff writer Carol Fowler describes the deplorable condition of

the Travis County International Cemetery which, like the poor farm, was used as

a pest camp from 1895-1909. Fowler states “Many persons who died of diseases

like smallpox and typhoid lie in unmarked graves on the land. Others were moved

to the land when the county sold the land on which the old poor farm had been

located.” and that “City records show…Between 100 to 200 bodies moved

from the county poor farm were buried in a common grave.”

The County has no records of the removals and reburials at either of the poor farms. A few names were determined by review of death certificates from 1915-1916:

Date of Death, Name, Sex, Race, Age:

December 31, 1912, Mrs. W. H. Davis, Female, N/A, 75

May 21, 1915, Juanita Hernandez, Female, White/Mex, 30

September 15, 1915, Conception Lontrassa, Female, Mexican, N/A

October 10, 1916, Salidad Rangel, Female, White, 6 mos.

November 27, 1916, Unknown, Male, Mexican, N/A

Clearly the development of Tarrytown

No 6. caused the removal of those 100 to 200 burials and it must have happened

are a very rushed pace to have had roads cut and houses erected 6 months after

Westenfield purchased in in June 1939. Deaths were reported at both the poor

farm and the International cemetery sites when they were used as pest camps,

but no records of burials. Add these to the known burials at the Swisher

Addition and Outlot 67 this brings the total unrecorded burial locations to 4 of

the 7 pest camp locations. The conclusion is that it is likely that there were

burials at all the camp sites and that the photographs of the 1916 Fort Prairie

pest camp burials are probably on the 16-acre tract where the tuberculosis

sanatorium was built in 1938-40.

|

| Figure 18- 1940 Aerial Fort Prairie Pest Camp #2 – The Last Pest Camp This 1940 Aerial Image shows the Sanitorium structure erected in 1938-1940. |

A history of the tuberculosis

sanatorium could be written on its own merit, but this closes the chapter of

the last pest camp. For current time perspective of the location and a summary

of the sanitorium, it opened in 1940 and was in operation until 1958. After

that the facility was operated as Brakenridge East until 1970, then as Girls Club

America until 1986, for a few years as a Salvation Army facility. In 2017 it

was renovated and repurposed as the Austin Shelter for Women and Children operated

by the Salvation Army. The Shelter located at 4613 Tannehill Ln, Austin, Texas.

On

January 28, 2021 TCHC commission members Bod Ward, Rich Denney and Lanny

Ottosen visited the shelter hosted by the shelter’s Residential Services

Director, and the shelter Maintenance Supervisor. The site visit was an

informal pedestrian survey of the grounds within the security fence around the

shelter. Almost all the 16-acre tract is developed except for the parameter outside

the fence including a ravine to the south of the shelter. Remains of a previous

house porch were observed to the southeast of the shelter reported to have been

a residence for the attending doctor. No signs of burials were observed. South

of the shelter outside the fence a dumpsite was observed that has construction

waste obviously placed there in recent decades. A few yards east of the

dumpsite an older dump was exposed in the bank from which iron cots were

observed.

|

| Figure 19- Metal cots in old dumpsite in a ravine east of the shelter. |

|

| Figure 20 -· July 24, 1907 Newspaper advertisement of similar metal cot. |

Near the end of the 19th

century there were “sanatory reform” programs being implemented across the

country. Out of this movement marketers of iron beds began advertising their

products as “sanitary beds” and “sanitary springs”, extoling their properties

as easier to sanitize that wood beds so cots of this type were common by 1900

and could have been used at the 1916 old pest camp or the sanatorium after

1940.[78]

The advertisement shown to the left closely resembles the cots observed.[79]

On March 23, 1917 Seaton's Sister Ursula Fenton wrote to her Mother Superior of their visit to the Fort Prairie Pest Camp that had been reopened stating that "Everything was new for sisters and nurses, tents [and] nice spring cots" [80]

|

| Figure 21 -Patent for a "Sanitary Cot". |

Whether the cots observed in the dump site are from the pest camp or the sanatorium, they are silent reminders of a bygone era of medical treatment at the last pest camp in Travis County. For over 100 years the grounds have been a foundation for aiding those in need.

Perhaps some of these cots should be recovered and preserved as a memorial to all who lost their lives in the pest camps of Travis County and to the doctors, nurses, chaplains and nuns that unselfishly cared for those in need.

END NOTES

[1] https://www.etymonline.com/word/pest / (accessed January 20, 2021)

[2] http://planomagazine.com/plano-smallpox-outbreak// (accessed January 20, 2021)

[3] Downs, Jim. 2012. Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering during the Civil War and Reconstruction, New York : Oxford University Press, ©2012

[4] Carlos E. Cuéllar, “Laredo Smallpox Riot,” Handbook of Texas Online, accessed February 09, 2021, https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/laredo-smallpox-riot. Published by the Texas State Historical Association. (accessed January 20, 2021)

[5] https://www.findagrave.com/cemetery/2491792/city-of-paris-pest-house-cemetery, http://www.lamarcountytx.org/cemetery_2/location/pesthouse.shtm, http://planomagazine.com/plano-smallpox-outbreak/, https://historic.one/tx/ellis-county/historic-cemetery/pest-house-cemetery, http://www.coloradocountyhistory.org/cemeteries/n-p.htm/ (accessed January 20, 2021)

[6] Figure 2 map Produced from 1940 Aerial Photos website: https://gis.traviscountytx.gov/portal1/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap=3fc65ce9029045349c5b3b0455416994 (accessed February 8, 2021) All other maps in this report produced from the Travis County TNR wedsite: https://geo.traviscountytx.gov/Html5Viewer/index.html?viewer=TNR_Map_Viewer.TNR_Web_Map (accessed February 8, 2021)

[7] Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · August 5, 1881, Page 2. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[8] “City Council Proceedings.” The Austin Daily Statesman. December 22, 1881; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Austin American Statesman pg. 3

[9] “SMALLPOX, Action of Board of Health”. The Austin Weekly Statesman (Austin, Texas). December 22,1881, Thu · Page 3. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 20, 2021)

[10] “THE SMALLPOX”. Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · December 29, 1881, Thu · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed December 29, 2021)

[11] “SMALLPOX, Report for the Day”. Mayor’s Office. Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · January 6, 1882, Fri · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[12] “BOARD OF HEALTH, Special Meeting at City Hall Yesterday”. The Austin Daily Statesman. February 10, 1882; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Austin American Statesman pg. 4

[13] “NEWS FROM THE TENTS, TELEPHONE CORRESPODNACE WITH THE CAMP. Questions Propounded to Dr. Denton and His Answers. A Full and Complete Report of Small Pox to Date.” The Austin Weekly Statesman (Austin, Texas) · January 19, 1882, Thu · Page 3 (accessed January 12, 2021)

[14] “Death of Miss Peterson.” The Austin Daily Statesman (1880-1889); January 15, 1882; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Austin American Statesman pg. 4

[15] “Another Death from Smallpox.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · January 6, 1882, Fri · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[16] “SMALL POX REPORT”, The Austin Weekly Statesman (Austin, Texas) · 9 Feb 1882, Thu · Page 3, https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[17] “REPORTORIAL, Matters and Things Laconically Noted.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · December 22, 1881, Thu · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 10, 2021)

[18] “The Swisher Addition.” Travis County Clerks Records, (Austin, Texas), Plat Book Volume 1, Page 2. May 26, 1877

[19] “CITY MATTERS IN BREIF.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · March 17, 1883, Sat · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[20] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 56, Page 139-140, book, 1882-09/1883-08; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth787639/: accessed January 16, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[21] “LOCAL SHORT STOPS, FRESH, CRISPY GLEANINGS OF RECENT NOTEWORTHY HAPPENINGS.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · April 3, 1886, Sat · Page 5. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 3, 2021)

[22] “THE SMALL-POX, ANOTHER NEGRO SENT OVER TO THE PEST CAMP.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · April 4, 1886, Sun · Page 6. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 11, 2021)

[23] “SMALLPOX RIOT, Farmers Prevent a Pest House From Being Located In Their Midst.” The Austin Weekly Statesman (Austin, Texas) · May 9, 1895, Thu · Page 2. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 6, 2021)

[24] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Clerk Records: Commissioners Court Minutes E, Page 47-473, book, 1883-08/1888-02; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth662106/: accessed January 16, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[25] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 73, Pages 582-583, book, 1886-12/1887-05; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth806885/: accessed January 16, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[26] “SMALLPOX. A Panic at Galveston Over the Alarming Spread of the Dreadful Disease” The Austin Weekly Statesman (Austin, Texas) · 31 January 1889, Thu · Page 9. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 31, 2021)

[27] “The Smallpox.” The Austin Weekly Statesman (Austin, Texas) · March 21, 1889, Thu · Page 5. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 20, 2021)

[28] Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · May 17, 1888, Thu · Page 9. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 21, 2021)

[29] “AUSTIN ILLUSTRATED.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · November 1, 1887, Tue · Page 2. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 21, 2021)

[30] November 1, 1887, The Chicago Illustrated Graphic News, Vol. VIII, No. 5, Cover Page, Courtesy of the Austin History Center, 1975:61

[31] “THE DRILL AND DEDICATION, An Important Meeting of the Directors Yesterday Afternoon.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · September 20, 1887, Tue · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 19, 2021)

[32] “OFFICIAL CIRCULAR, GENERAL INFORMATION.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · February 5, 1888, Sun · Page 3. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 21, 2021)

[33] “DRILL BOARD MEETING, Business Transacted – Outline of the Prospectus, etc.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · September 25, 1887, Sun · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 21, 2021)

[34] “Timely Advice.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · January 7, 1891, Wed · Page 3. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[35] “Everything Fixed for Smallpox.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · January 7, 1891, Wed · Page 2. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 7, 2021)

[36] “THE SMALLPOX, OUR FAIR AND BEAUTIFUL CITY FREE OF THE DISEASE, CAMP PALMER TO BREAK TODAY.”Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · May 20, 1891, Wed · Page 3. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[37] “THE SMALLPOX, ANOTHER CASE SERENELY BOBS UP IN THE CITY YESTERDAY.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · January 16, 1891, Fri · Page 3. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[38] SMALLPOX: DANGEROUS CARELESSNESS AT CAMP PALMER--PERMITS INFECTED...The Austin Statesman (1889-1891); April 14, 1891; ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The Austin American Statesman pg. 4

[39] “THE STATE HEALTH OFFICER, What He Has to Say of the Disease After A Personal Examination.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · April 18, 1891, Sat · Page 3. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 20, 2021)

[40] Minutes of Regular Meeting of the City Council, Austin, Texas, June 1, 1891 & Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · 2 Jun 1891, Tue · Page 5. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[41] “Claim of W.H. Tobin for Damages by Smallpox Camp.” August 7, 1893, The Minutes of a Regular Meeting of the City Council, Hon John McDonald, Mayor Presiding, Austin, Texas

[42] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 91, Page 222, book, 1889-01/1890-02; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth806888/: accessed January 24, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[43] “THE JUDICIAL HARVEST, BUSINESS TRANSACTED IN THE TWIN DISTRICT COURTS YESTERDAY”. Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · 20 November 1891, Fri · Page 5. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 3, 2021)

[44] “THE PEST CAMP.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · April 23, 1895, Tue · Page 3. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 7, 2021)

[45] Sunday, March 5, 2017, Richard Denney, Travis County Historical Commission Blog, Poor Farm: Travis County's First https://traviscountyhistorical.blogspot.com/search/label/Poor%20Farm%3A%20Travis%20County%27s%20first%20near%20Spicewood%20Springs

[46] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 43, Pages 613-615 book, 1878-01/1879-07; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth787613/: accessed January 26, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[47] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Clerk Records: Commissioners Court Minutes G, Page 409, 417-418, 423 & 464-465, book, 1892-02/1897-05; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth662104/: accessed January 24, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[48] “THE COUNTY COMMISSIONERS.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · April 4, 1895, Thu · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 16, 2021)

[49] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 134, Page 13, book, 1895-05/1897-10; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth864795/: accessed January 24, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[50] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Clerk Records: Commissioners Court Minutes G, Page 409, 417-418, 423 & 464-465, book, 1892-02/1897-05; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth662104/: accessed January 24, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[51] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 134, Page 13, book, 1895-05/1897-10; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth864795/: accessed January 24, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[52] “PICKED UP ABOUT TOWN.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · May 20, 1909, Thu · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 17, 2021)

[53] “PICKED UP ABOUT TOWN.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · December 9, 1908, Thu · Page 4. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 24, 2021) & Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 232, Page 98-100, book, 1908-10/1909-01; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1110903/: accessed January 26, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[54] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Clerk Records: Commissioners Court Minutes K, Pages 132-133 book, 1906-12/1913-05; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1110922/: accessed January 26, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[55] “PICKED UP ABOUT TOWN.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · February 7, 1909, Sun · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 26, 2021)

[56] “PEST CAMP AT COUNTY FARM IS ABOLISHED.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · March 21, 1909, Sun · Page 7. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 17, 2021)

[57] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Clerk Records: Commissioners Court Minutes K, Pages 182-183, book, 1906-12/1913-05; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1110922/: accessed January 24, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[58] “PICKED UP ABOUT TOWN.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · August 31, 1910, Wed · Page 10. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 17, 2021)

[59] Holden, Nellie J.,“TO DISCOURAGE BEGGING MODERN CHARITY PLAN” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · November 22, 1914, Sun · Page 24. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed February 1, 2021)

[60] “MEXICANS QUARANTINED.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · March 3, 1912, Sun · Page 2. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 17, 2021)

[61] “LIVE TOPICS ABOUT TOWN.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · March 5, 1912, Tue · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 13, 2021)

[62] “LIVE TOPICS ABOUT TOWN.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · March 6, 1912, Wed · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 17, 2021)

[63] “LIVE TOPICS ABOUT TOWN.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · March 7, 1912, Thu · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 13, 2021)

[64] “PICKED UP ABOUT TOWN.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · October 12, 1912, Sat · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed February 1, 2021)

[65] “TUBERCULOSIS CAMP IS TOPIC DISCUSSED, NURSE EMPLOYED FOR CONSUMPTIVES DOWN BY THE RIVER.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · November 15, 1912, Fri · Page 2. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 4, 2021)

[66] “MAY MOVE CONSUMPTIVE CAMP TO EAST OF CITY. COUNTY COMMISSIONERS OFFER SHADY TRACT.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · June 19, 1913, Thu · Page 2. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 6, 2021)

[67] “MAYOR COMMENDS WOMEN FOR SERVICES TO SUFFERERS.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · August 18, 1913, Mon · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 6, 2021)

[68] “Nineteen Persons Live in Hovel in Abject Poverty; Man Victim of Consumption.” The Austin American (Austin, Texas) · November 6, 1914, Fri · Page 10. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 12, 2021)

[69] “CITY AND COUNTY PROPOSE TO HAVE JOINT PEST CAMP.” The Austin American (Austin, Texas) · June 23, 1916, Fri · Page 6. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 17, 2021)

[70] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 294, Pages 350-351, book, 1917-02/1917-06; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1212448/: accessed February 1, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[71] “SMALLPOX CASES HERE ARE SIX. Thirty-Six in Pest Camp Doctors Advise Vaccination.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · 28 February 1917, Wed · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 13, 2021)

[72] “SMALLPOX NOW UNDER CONTROL. City Will Soon Be Free of the Dreaded Disease.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · May 11, 1917, Fri · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed February 1, 2021)

[73] “TRAVIS COUNTY SMALLPOX CAMP IS CLOSED.” Austin American-Statesman (Austin, Texas) · June 1, 1917, Fri · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 17, 2021)

[74] September 1984, Jackson Historical Cemetery, Los Lomas Subdivision, Epsey, Huston & Associates, Inc., Document No. 84679, EH&A Job No. 5364, Austin, Texas

[75] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Clerk Records: Commissioners Court Minutes H, Page 597, book, 1895-02/1919-10; (https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth662099/: accessed February 1, 2021), University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu; crediting Travis County Clerk’s Office.

[76] “COUNTY SELLS POOR FARM for $24,500” The Austin American (Austin, Texas) · June 1, 1939, Thu · Page 17. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 24, 2021)

[77] Travis County (Tex.). Clerk's Office. Travis County Deed Records: Deed Record 232, Pages 1

[78] “Getting the House Ready for Fall and Winter” The Lancaster Examiner (Lancaster, Pennsylvania) · 17 September 1902, Wed · Page 8. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 30, 2021)

[79] “BRENT’S, Closing Out Our Entire Stock.” Los Angeles Herald (Los Angeles, California) · July 24, 1907, Wed · Page 2. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 30, 2021)

[80] Letter dated March 23, 1917 form Sister Ursula Fenton to Sister Visitatix RG 7-6-1, Epidemics Collection, Daughters of Charity Archives, Province of St. Louise, Emmitsburg, MD

[81] July 25, 1916, Sanitary Cot, F.S. Inco, US Patent Number 1192318 https://patents.google.com/patent/US1192318, (accessed January 30, 2021)

[82] “Nurses Receive Medals for Faithful Service" The Austin American (Austin, Texas) · July 8, 1917, Sun · Page 11. https://www.newspapers.com/ (accessed January 6, 2021)

No comments:

Post a Comment